Black Americans in Early Oregon City (1841 - 1864)

While the western migration over the Oregon trail largely consisted of white re-settlers, many Black emigrants settled in the territory both prior to and during the “Great Migration.” Some were enslaved persons seeking freedom, while others were free men looking for opportunity, and others still were brought to the region by happenstance. Because of the city’s standing as the territorial capital, Oregon City became the place many of these individuals settled, even if only for a short time. Still, while the territory had officially prohibited slavery in 1843, the white population largely disapproved of Black settlement, leading Oregon City’s Black residents to face constant struggle. The first Black Exclusion laws were put in place to discourage Black migration in 1844, and in 1849 even more exclusion laws were introduced to the state constitution, officially barring Black residents from living in the territory.

Despite these racist legislations, many Black Americans still chose to settle in Oregon: an 1860 census counted 128 Black individuals residing in the region. These entries were compiled from our social media series highlighting the stories of Black Americans in Clackamas County during the summer of 2020, and are meant to give a broad timeline of notable individuals who resided in Oregon City during its early period. If we are to fully comprehend our city’s history, we must learn of the injustices our earliest Black residents faced, and how racist policies shaped and continue to shape our region in the modern day.

USS Peacock in Antarctic ice, by Alfred Thomas Agate; Public domain. Description: an 1800’s wooden schooner sails through large icebergs, a large ice cliff to its back.

James D. Saules

Arrived in the Oregon Territory in 1841

Estimated to have been born in 1806, James D. Saules was a free Black musician and sailor who arrived in Oregon in 1841 while serving aboard the USS Peacock (pictured). The Peacock was part of the US Exploring Expediton, an effort by the US government to more accurately map the Pacific Northwest, as well as “expand American influence.” The ship was smashed to pieces in July while attempting to sail the Columbia River, and although Saules and his fellow crewmates survived, they were now stranded. Three months later the crew continued the expedition aboard the brig Oregon, but Saules instead chose to remain, and by 1844 he had married a Chinook woman and was living near the Willamette Falls.

Unfortunately, it was during the period that Saules would become involved in an event known as the Cockstock Incident. Saules was then later accused of inciting violence towards a pro-slavery resident and was told to leave the Willamette Valley by Elijah White, the subagent of Indian Affairs. White would infamously describe Saules and his fellow Black Americans as “dangerous subjects” in a letter to the US Secretary of War, and inquired about instituting a ban on Black Americans in the territory. One month later, on June 26, 1844, Oregon would pass its Black Exclusion Law.

Little is known about Saules after his removal from Oregon City. He lived for a short time at Cape Disappointment in Washington but was later forced to move after two white settlers claimed the land. In 1846 he was brought back to Oregon City after being accused of having a hand in his wife’s death but was later released from custody. He disappeared from the record altogether in 1850, with some historians believing him to have drowned in 1851.

Rose Jackson; CCHS collection.

Rose Jackson

Arrived in the Oregon Territory in 1849

Many emigrants traveled over the Oregon Trail in the early to mid-19th century, but of them we are only aware of one who made the journey inside a crate: such is the story of Rose Jackson, who emigrated from Missouri with Dr. William Allen and his family in 1849. While the Allens were free to roam along the trail as they pleased, Rose was confined to a wooden box with ventilation holes. Rose was enslaved by Dr. Allen and, due to Oregon’s Black Exclusion Laws, bringing Rose into the territory was illegal. Initially Allen had opted to leave Rose behind, but she convinced the family to bring her with them, with the condition being that she remain hidden during the day. Upon arriving in Oregon Rose was freed, though she still remained in contact with the Allens. As William Allen had passed not long after completing the journey, Rose helped the family survive their first winter by working as a laundress, reportedly sharing as much as $12 with them per day (estimated to be over $350 in today’s money). While living in Clackamas County she met her husband, John Jackson, a horse groomer who operated in Oregon City. They had two children and eventually settled in the Waldo Hills of Marion County.

Article XVIII, from the State Constitution, 1857; Oregon Historical Society

Jacob Vanderpool

Arrived in the Oregon territory in 1850

As we highlight the stories of Black Americans in Oregon City, it’s important that we address the racist legislation that threatened the livelihoods of Black American emigrants in our region, and the man whose right to liberty was denied through its enforcement.

Like many hopeful emigrants, Jacob Vanderpool arrived in the Oregon Territory in the mid-nineteenth century. A sailor by trade, Vanderpool was born in the West Indies in 1820 and had come to the territory aboard the ship Louisiana. He became a resident of Oregon City, and during this period he owned and operated the Oregon saloon and boarding house within the city. However, Vanderpool’s residency was cut short: in 1851 a white settler named Theophilus Magruder brought charges against Vanderpool for illegally residing in the territory. White settlers had voted in legislation in 1849 that prohibited Black Americans from legally living within the territory, now referred to by contemporary historians as the Black Exclusion Laws. While we cannot know his motives for certain, it is possible, if not probable, that Magruder intended to eliminate Vanderpool as a business competitor, as Magruder had opened his own hotel in Oregon City only one short month before pressing charges. Whatever his motivations, the consequences of Magruder’s actions were immediate: Vanderpool was promptly arrested by U.S. Marshal Joseph L. Meek and put on trial. Three witnesses were brought in to testify for Vanderpool’s defense, but it could not persuade Territorial Judge Thomas Nelson, who swiftly ordered Vanderpool’s removal. The arrest and proceedings took a total of six days. Jacob Vanderpool is the only Black American known to have been forcibly removed via Oregon's Black Exclusion Laws- laws would not be repealed until 1926.

George Washington with his dog, Rockwood; Washington Historical Society

George Washington

Arrived in the Oregon Territory in 1850

George Washington, the founder of Centralia, is a name that is likely familiar to our neighbors in the state of Washington, but he was also once a citizen of Oregon City. Born in Virginia in 1817, George was raised by James and Anna Cochran, a white couple, after his mother entrusted them with his care. He spent some of his childhood in the state of Missouri, where the Cochrans successfully petitioned on George’s behalf to grant him the full rights of citizenship, minus the right to vote. In 1850 he and the Cochrans traveled over the Oregon Trail and settled in Oregon City, however the Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon forced them to migrate north, into what was then known as the Northern Oregon Territory. When concerns arose that George might still be forcibly removed by the government, over one-hundred of his fellow citizens petitioned to have George remain. In 1853 the Washington Territory was created, its legislation lacking the same anti-black land-owning laws as the Oregon Territory. In 1875 at the age of 58, George and his wife Mary Jane founded the town of Centerville, known today as Centralia.

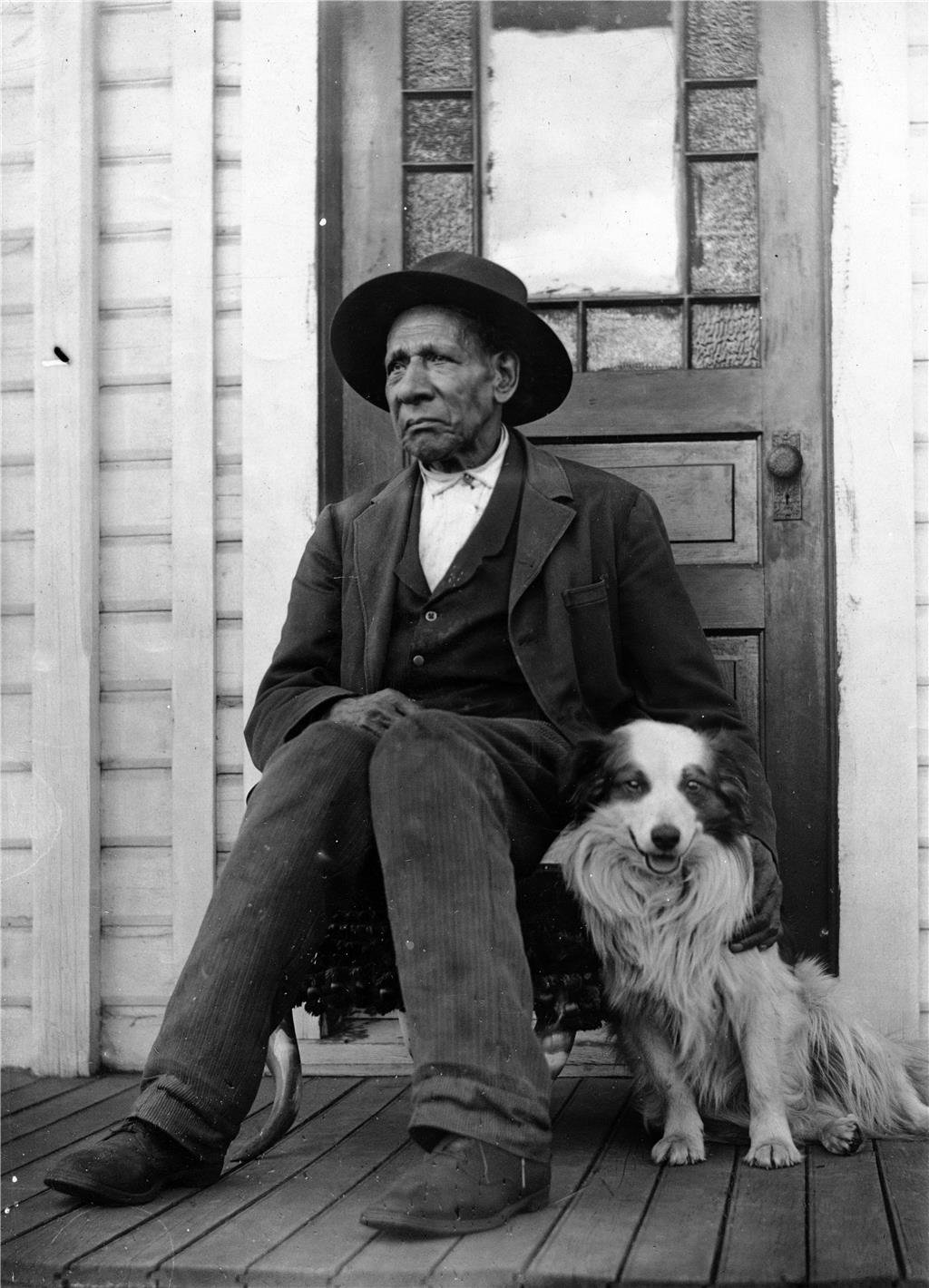

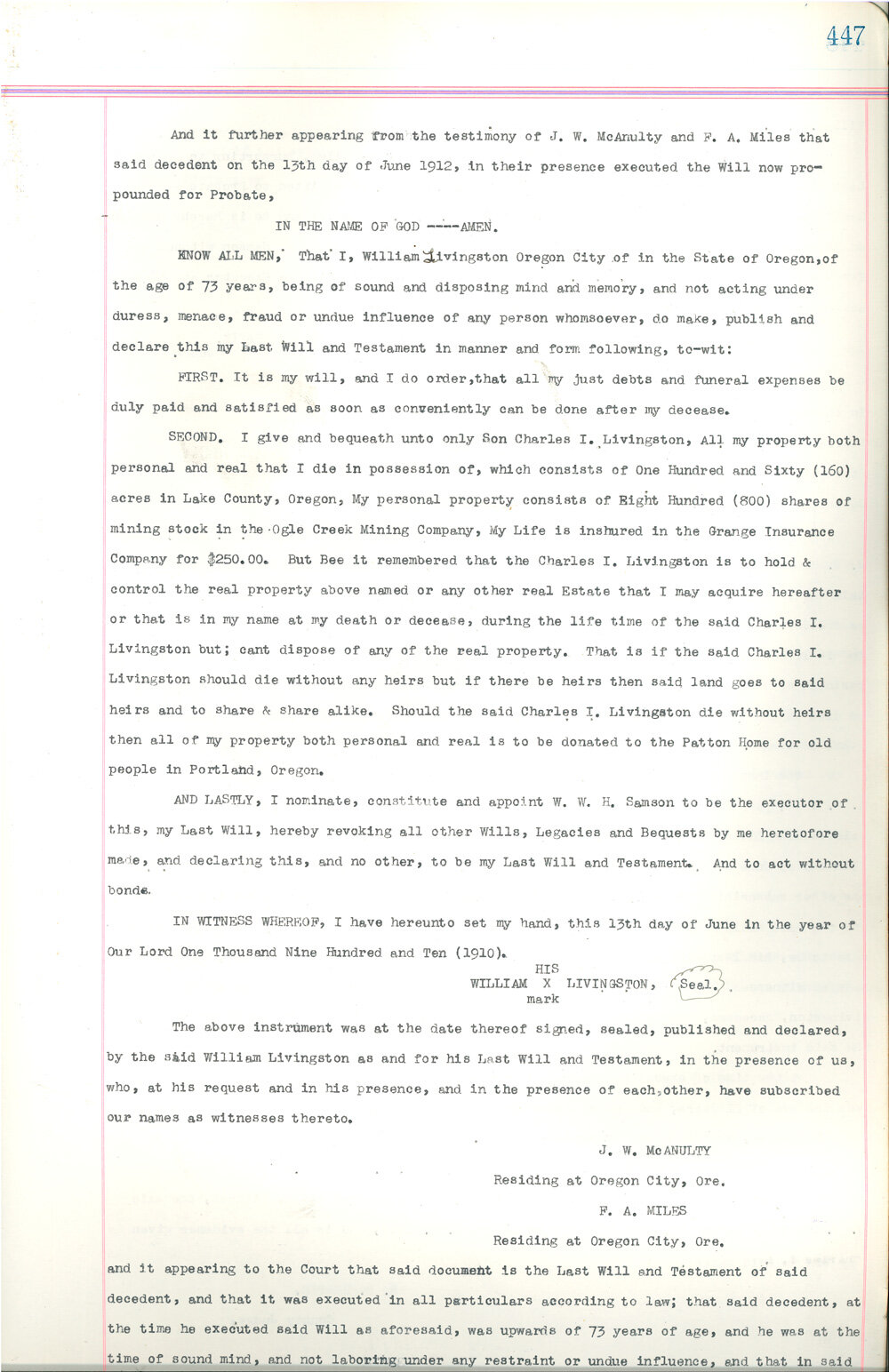

William “John” Livingstone, CCHS collection

William “John” Livingstone

Arrived in Oregon in 1864

Hailing from Missouri, William “John” Livingstone spent his early life enslaved to a man by the name of Judge Joseph Ringo. Having grown up in the town of Hannibal, according to Livingstone’s obituary in the August 13, 1912 edition of the Morning Oregonain, he was a childhood friend of Samuel Clemens, better known by his pen name Mark Twain. At the age of 27, one year before the end of the Civil War, John was emancipated, and the following year he would accompany the Ringo family on their journey to Oregon. Upon arrival Livingstone immediately proved his entrepreneurial spirit, earning money by transporting lumber from Oregon City’s upper bluffs to the steadily expanding downtown district. He used his funds to purchase property in the Clackamas County area and beyond, which he then sold to other emigrants, even selling 128 acres to Ringo in 1872. When John died at the age of 76, he owned 160 acres of property in Lake County, had 800 shares of the Ogle Mining Company, and his estate was valued at $15,000- equivalent to $380,000 in today’s money. It’s reported that attendance at his funeral was in the hundreds, and the August 10, 1912 obituary in the Oregonian said of Livingstone, “No man in the county was more respected, and no man had a better reputation for honesty.”

Updated May 28, 2022: this article was updated to reflect recently published research that demystified the life and story of Jacob Vanderpool, as well as minor grammar and spelling corrections.